Overview:

What is Accounting? Webster’s Dictionary defines accounting as: “The system of recording and summarizing business and financial transactions and analyzing, verifying, and reporting the results”.[1]

Purpose:

This article will give some of the basic key principles of accounting. There are many forms of accounting, but for now, we’ll talk about the United States of America Generally Accepted Accounting principles, US GAAP. However, most forms of accounting, such as International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) (which is used in many countries), have similar principles.

The first decision to make in accounting is if you want to account for your business (or personal life) as cash or accrual basis of accounting. Cash basis accounting is based upon whether you receive or pay cash. Accrual basis accounting is based upon when revenue is earned or the services are incurred and not when cash is received or cash is paid.

Analysis # 1:

Let’s do a quick example to show how cash vs. accrual basis accounting works. Let’s show how an individual accounts their monthly electric bill. You sign up for a new electric plan for October. You used the electric in October, but the bill was not due to be paid in cash until November. Under cash basis accounting, there would be no expense in October because there was no cash paid in October. In accrual basis accounting, since the electric was incurred in October, we would have electric expense in October and a liability due to the electric company. US GAAP requires the use of accrual basis accounting whereas US Tax returns usually use cash basis accounting.

Analysis # 2:

Now that we’ve discussed the differences between cash and accrual basis accounting, let’s go into other key principles of accounting.

Some key terms in accounting:

– T Account – Tracks all the debits and credits and allows anyone to see what the balance in an account at any point in time.

– Debits – Left side of a T Account, shown as a positive.

– Credits – Right side of a T account, shown as a negative.

– Assets – these are things we own. They hold a debit balance and some examples of common asset accounts are: Cash, Account Receivable and Fixed Assets.

– Liability – these are what we owe others. They hold a credit balance and some examples of common liability accounts are: Accounts Payable, Mortgage Liability and Interest Payable.

– Equity – this is the company’s or individual’s net worth. They hold a credit balance if we have positive net worth or a debit balance if we have a negative net worth. Some examples of common equity accounts are: Dividends, Net Income and Common Stock.

– Revenue – these are income to the company. They hold a credit balance and some examples of common revenue accounts are: Sales, Interest Income and Gain on Sale.

– Expense – these are costs to the company. They hold a debit balance and some examples of common expense accounts are: Cost of Goods Sold, Marketing Fees and Interest Expense.

– Any revenue and expense accounts roll into our equity account called Retained Earnings. Thus, all accounts that are part of the “Income Statement” (revenue & expense) will be part of equity.

The most important principles (done as equations) are:

1) Assets = Liability + Equity

2) Debits = Credits

Overall accounting is based upon a 2-line entry system of a debit and a credit. Each time we make a journal entry we are either increasing or decrease the balance of an account.

Analysis # 3:

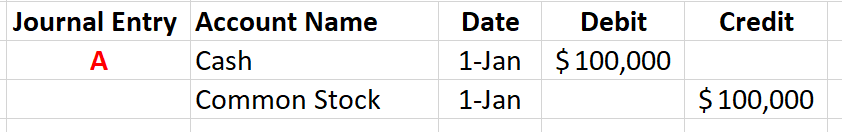

In order to see this in practice, let’s walk through a couple entries of our MFC Pizza Company.

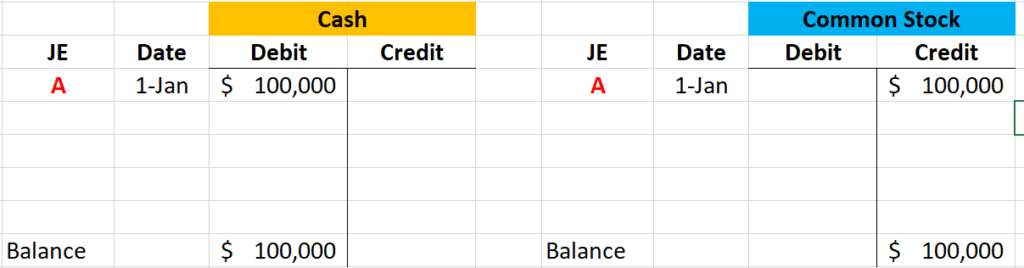

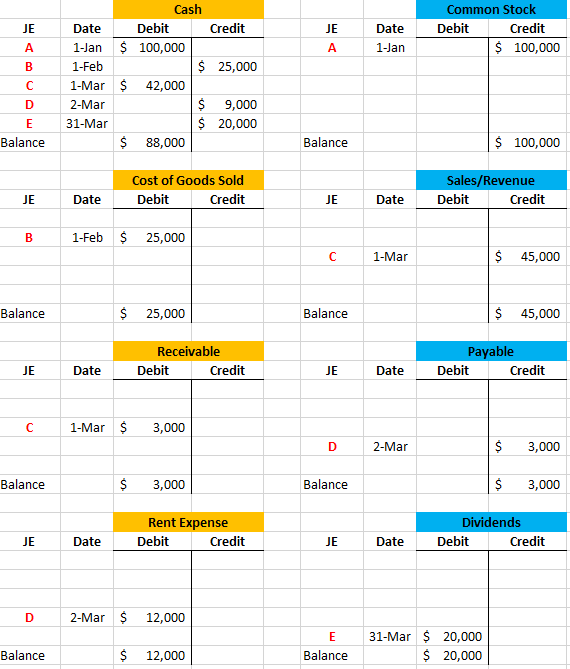

Here is the running T Accounts of our MFC Pizza Company:

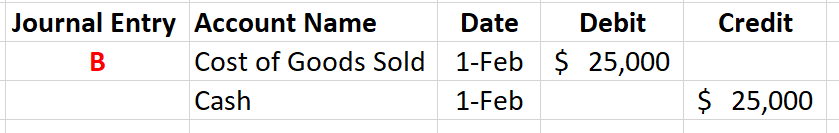

B) On February 1st, we’re going to buy pizza dough, cheese, tomato sauce and other materials. We found a vendor (what we call a company from which we purchase goods from) that we will pay $25,000. Thus, we will have a decrease in the cash account of $25,000. Since cash is an asset account, a decrease in an asset account is created by a credit to the account. Our ingredients for the pizza will be an expense and part of an account called Cost of Goods Sold. Expenses increase by a debit; thus, we’ll debit this expense account for $25,000. See the second most important accounting equation still holds that debits equal credits

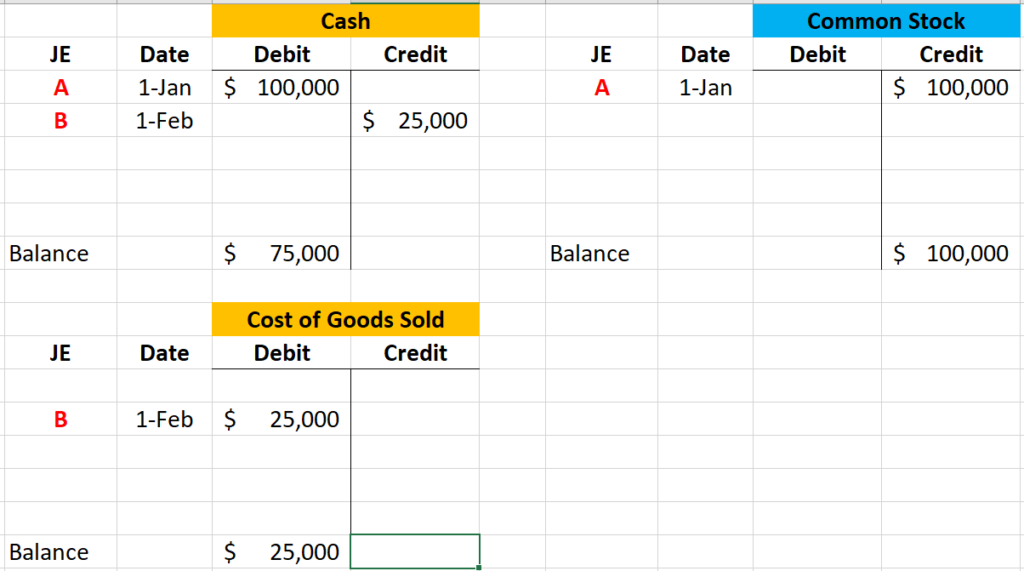

The T Accounts of our accounts to date will look as follows:

Notice that we now have a new account, Cost of Goods Sold in our T Accounts. Our balance as of February 1st in the cash account has now changed to $75,000. This is because the account has a debit of $100,000 followed by a credit of $25,000 for a net balance of $75,000.

Also, the important accounting equation of Assets = Liability + Equity still works. Thus Assets (our cash account) would equal $75,000. The other side of the equation would equal $75,000 as we have a credit balance of $100,000 from the Common Stock account minus debit balance of $25,000 from the Cost of Goods Sold account.

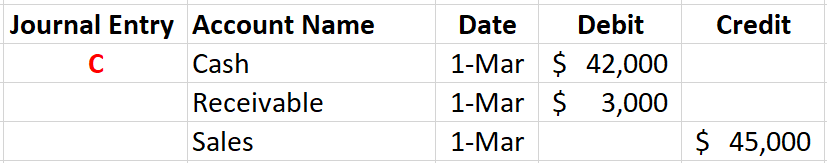

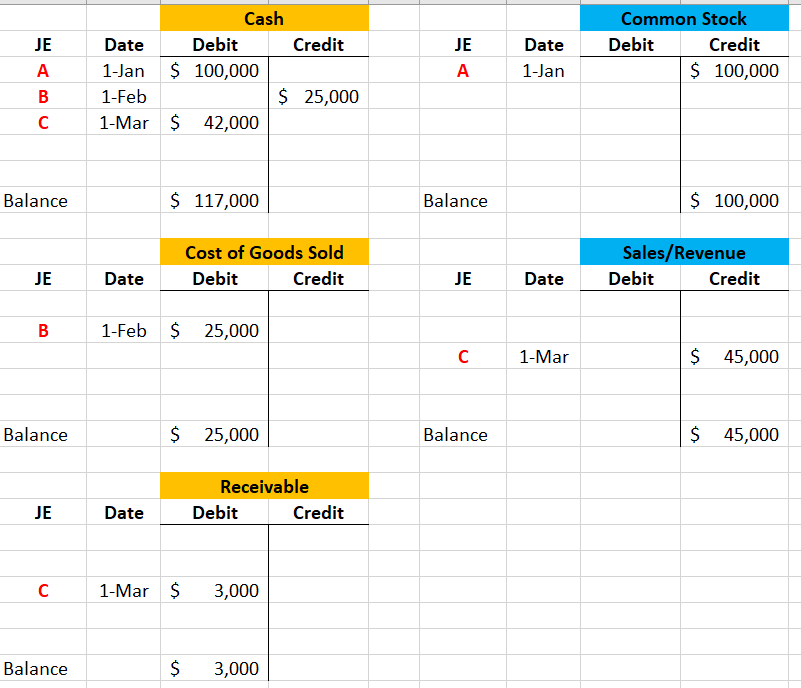

C) On March 1st, we’ll make our first big sale of pizza for $45,000. It’s a one-time sale, so our customer is going to pay us almost all upfront, except for $3,000. Therefore, we now have a receivable from our customer of $3,000, sales of $45,000 and have increased our cash by $42,000 (from $75,000 to now $117,000). This is a change from my original discussion point about journal entries being a 2-line entry systems. But now since you’re an accounting expert, we’ll update this accounting principle to state that a journal entry must contain at least 2 lines. There is no true limit to the amount of lines in one journal entry, but the key is always that debits equal credits and again in this example that principle still holds true.

We’ve now added a few more accounts, Receivable & Sales and thus the number of accounts is really growing.

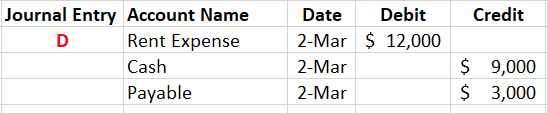

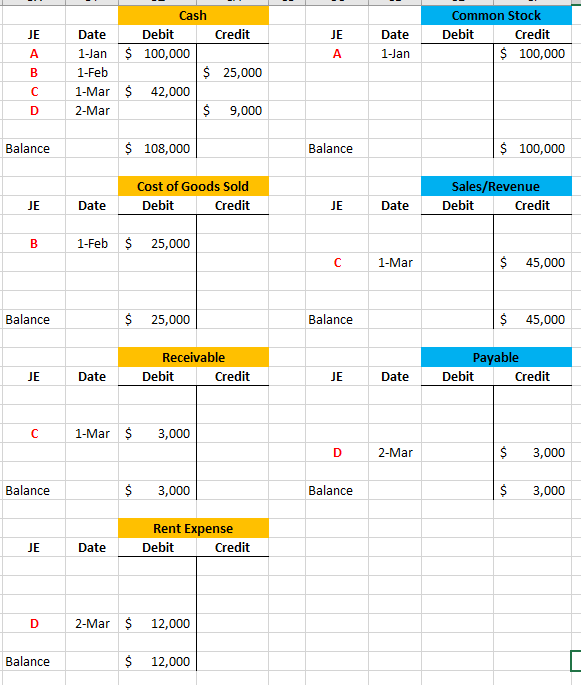

D) As we’ve now made our first sale in our shop, the rent for our store is now due, which is $12,000 per month. Since our landlord knows were just starting off, he’s giving us a break and only requiring us to pay cash for 75% of the rent on March 2nd, with the last 25% due April 1st. Thus, we will pay out cash of $9,000 and have a liability (or payable) of $3,000 to the landlord. Our total rent expense would be $12,000 for the month. Again, we’ll have another journal entry with more than 2 lines.

In our T Accounts, we’ve now added another 2 accounts and I can barely fit them on one snip. Thus, when we look at accounts, its easier to look at accounts at the balance level and then dig into the T Accounts to see the account balances and transactions to date for MFC Pizza Company.

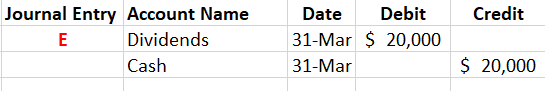

E) On March 31st, the month is done and you as the owner would like a payment of cash. You could pay yourself via payroll, but (for this example) we’ll pay you as the owner a cash dividend of $20,000. Thus, we have another new account, Dividends. Dividends are a contra account of equity, and Dividends have a debit balance compared to other equity accounts that usually have a credit balance.

There’s our final T-accounts through end of March.

Conclusion:

As this is just the basic beginning of your understanding of accounting, lets go back over some of the key principles and topics we learned via this article:

– Assets = Liabilities + Equity;

– Debits = credits;

– Cash is involved in most entries;

– The number of accounts can get long very quickly; and

– Looking into a balance of an account first and then digging into the transactions will help you review an accounts history.

Action Plans:

This is just the very basics of accounting, but these simple principles are the building blocks for all of accounting. For next action steps:

– Take a basic accounting class;

– Review a company’s 10k and check over the accounts used on the Balance Sheet, Income Statement and Statement of Equity; and

– Review other accounting topics and articles on Finance First.