Mutual Fund Fees

Overview:

The world of retirement has changed away from a pension and social security system directed by your employer to IRA and 401(k) system directed by an employee. It is now on the employee to understand the inputs and outputs of their retirement, as nothing will be handed to employees the way pension and social security are today. The subject of today’s article is mutual fund’s fees, as mutual funds usually make-up an employee’s retirement account. {Noted that mutual funds are also included throughout other investment vehicles like 529 plans and mutual funds are also a favorite of financial advisers}.

Purpose:

There are many great articles around the different types of investment fees, but for this article, I just want to put out an example of how a mutual fund takes away an employee’s retirement money via the fees they charge. For now, we’re just going to talk through the yearly expense a mutual fund typically charges. My current Audio Book is actually “Common Sense on Mutual Funds” by John Bogle (the man who started Vanguard), so I plan on adding a few more articles around the types of fees charged by a mutual fund and overall discussion on mutual fund to Finance First.

Assumptions:

So, let’s do a quick example of how your mutual fund fees will take your retirement. Let’s start with the following Finance First Assumptions:

- The employee will start contributions at age 30;

- The employee will make a contribution of $100 per month in the first year and then yearly will increase the contribution by 3% per year (thus at year 2 the per month contribution will be $103). We consider the 3% per year increase reasonable as it is in line with inflation and the possible employee raises seen in the market. We’ll name this investment vehicle the “Employee Plan”;

- The employer’s 401(k) plan will only allow the employee to contribute to a mutual fund that has 2%[1] yearly fees as part of their operations. We’ll assume the mutual fund is able to reinvest all the fees in the stock market. (While they might have some expenses, this % is just used to show how an index fund with little fees would greatly outperform the mutual fund, thus for this purpose we just need to stretch the assumption a little bit). Further I’ve used a higher rate than average so that I can show how not only high fees affect you, but also that the SEC even calls out high mutual fund fees on its website: “Higher expense funds do not, on average, perform better than lower expense funds.”[2] We’ll name this investment vehicle the “Fee Balance”;

- The yearly growth will be 7% which is a reasonable growth rate of investment in stocks[3] and will be the rate used by both the Employee Plan and the Fee Balance throughout the periods reviewed; and

- The employee will retire at age 65, stop contributions and withdraw $30,000 per year (for now we’ll keep out the fact that inflation has really hurt the employee’s life style, but that’s for another article);

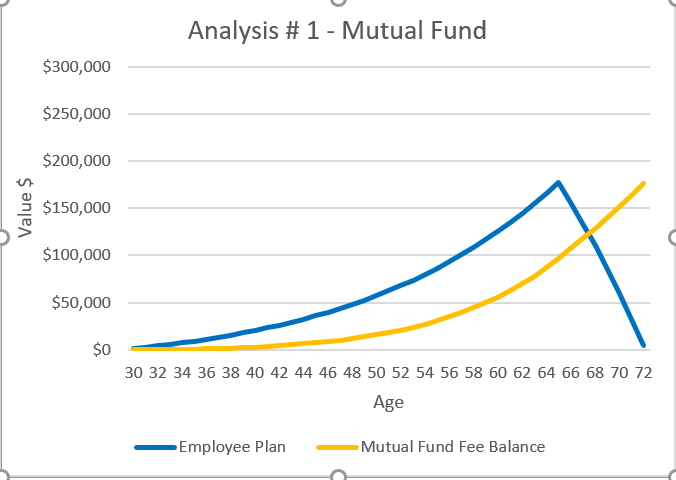

Analysis # 1

So, let’s run the numbers excluded in the Finance First Assumptions and see how the employee ends up in retirement:

- By age 65, the Employee Plan will be worth $177,377. The Fee Balance will be worth $96,297. Thus, the mutual fund will own 35% of your retirement. Yes, you read that right, you’ve given the mutual fund 35% of your hard-earned money;

- By age 72, the Employee Plan will only be worth $4,045 left. The Fee Balance will be worth $175,795. Thus, the mutual fund will own then 100% of the employee’s retirement; and

- The employee’s total cash contributions would be $75,931 which the employee paid $60,816 of fees and would have been able to take $210,000 of cash distributions. The mutual fund, by just getting those $60,816 of fees, will be able to turn the employee’s money into $175,795, which will be 46% of the employee’s retirement;

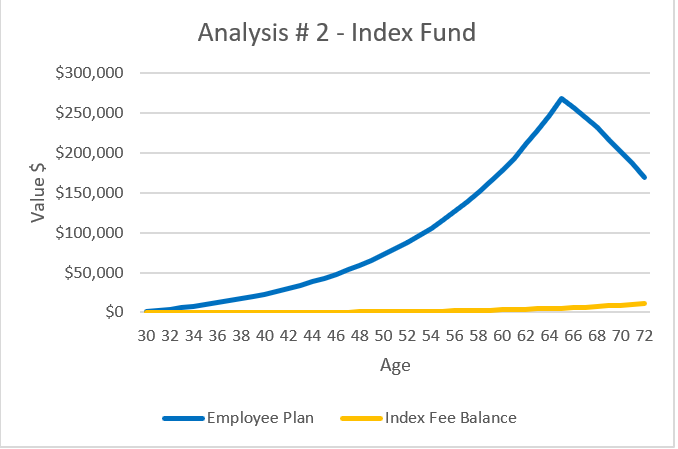

Analysis # 2

So now, rather than investing in a mutual fund, we’ll slightly change the assumptions and the employee will invest in the SPY index fund which has minimal fees of .09%[4] vs. mutual funds of 2%. The employee’s retirement would look like:

- By age 65, the Employee Plan will be worth $268,199. The index fee balance will be worth $5,475. Thus, the index fund will own 2% of the employee’s retirement, which sounds a lot better than the 35% in Analysis # 1;

- By age 72, the Employee Plan will be worth $169,105. The index fee balance will be worth $10,735. Thus, the index fund will own 6% of the employee’s retirement; and

- The employee’s total cash contribution would be $75,931 which the employee paid $4,229 of fees and would have been able to take $210,000 of cash distributions. The index fund, by getting those $4,229 of fees, will be able to turn the employee’s money into $10,735, which will be 5% of the employee’s retirement.

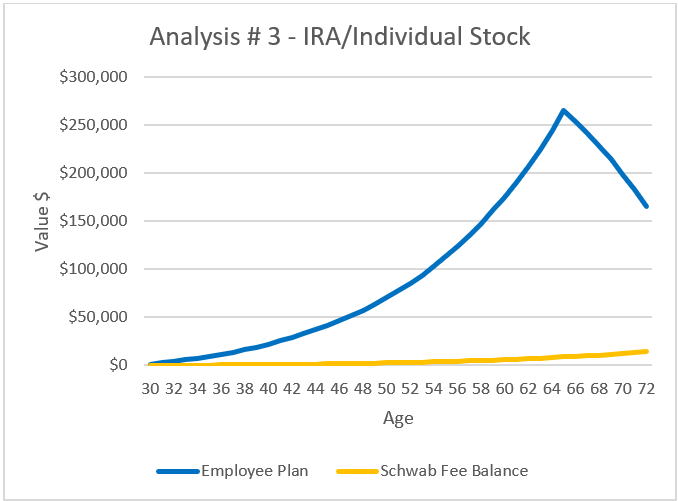

Analysis # 3

So last let’s assume instead of the assumption in Analysis # 1 & 2, the employee invests monthly in one individual stock in an IRA. We’ll use Schwab which has fees of $4.95 per trade[5] as our basis for the fees in an individual stock in an IRA. If the employee did 12 trades a year at $4.95 per contributions over 36 years, the employee would have been charged $2,138 of fees. The employee’s retirement would look like:

- By age 65, the Employee Plan will be worth $264,828. The Schwab fee balance will be worth $5,475. Thus, Schwab will own 2% of the employee’s retirement, which sounds a lot better than the 35% in Analysis # 1;

- By age 72, the Employee Plan will be worth $165,636. The Schwab fee balance will be worth $14,204. Thus, Schwab will own 8% of the employee’s retirement; and

- The employee’s total cash contribution would be $75,931 which the employee pays $2,138 of fees and would have been able to take $210,000 of cash distributions. Schwab, by getting those $4,229 of fees, will be able to turn the employee’s money into $14,204, which will be 6% of the employee’s retirement.

Conclusion:

As you can see a mutual fund’s fees are something most employees don’t understand how the fees affect their retirement. They assume a 2% fee mean that mutual funds only will own 2% of their retirement whereas we’ve proven above that the mutual fund will really own 35% of your retirement in our example. Thus, an employee must really understand what fees they are really paying and what they are getting from those fees to make sure their hard-earned money goes to them.

Action Plans:

So, what can an employee do if their employer only has a 401(k) plan that offers mutual fund as the only investment vehicle:

- Review the employer’s 401(k) mutual fund and see if the fees are at least as low as the SPY index fund;

- Reach out to your employer and ask them to review their investment strategies and open the plan to indexes and EFT’s. Present this, or many other examples, on how employees are losing money due to mutual fund fees;

- If you leave your job, you can do a roll-over into an IRA and thus really take ahold of your investments as the employee and will not be subjected to hidden fees from your current employers 401(k) plan;

- Check if your available for Roth retirement features; and

- Especially if you’re in a lower tax bracket and if your company doesn’t match contributions, do an analysis to see if you should make investments in stocks/bonds that don’t have a tax deferral portion to them (i.e. just normal investments). While the 401(k)-tax deferral is great, if you’re in a lower tax bracket, the tax deferral is not saving you too much money now and you can avoid losing your retirement to mutual fund’s fees. Further, this will keep the money from being trapped in a tax deferred asset that if you need the cash will have high penalties.

Charts:

Footnote:

[1] https://www.investopedia.com/university/mutualfunds/mutualfunds2.asp

[2] https://www.investopedia.com/university/mutualfunds/mutualfunds2.asp

[3] Taken per total real rate of return from: http://www.simplestockinvesting.com/SP500-historical-real-total-returns.htm

[4] https://www.fool.com/investing/etf/2013/09/09/the-4-cheapest-etfs-for-buying-us-stocks.aspx

[5] https://www.schwab.com/public/schwab/investing/accounts_products/accounts/brokerage_account